Michael Kernahan: A Life in Pan

By Dr. Stephen Stuempfle, Historical Museum of Southern Florida

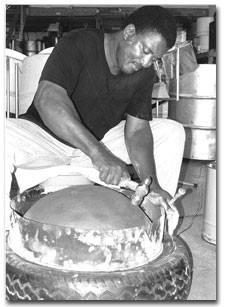

In a field of sawgrass behind a warehouse complex on the edge of Miami's suburban Tamiami Airport, Michael Kernahan creates high-precision musical instruments, known as pans, from discarded oil and chemical barrels. He works in a small clearing under a tree that provides some limited shade. Assorted barrels are stacked around the space-some are full size, while others have been cut. A briefcase filled with metalworking tools rests on one barrel. From the edge of the clearing, a narrow path extends to another space, where pans are heated over a wood fire. In the distance is a third clearing, in which Kernahan's apprentice, Michael Phillip, sometimes works. This outdoor workshop is a peaceful place. Breezes blow across the acres of sawgrass, while occasional helicopters and small planes take off from the airport. The surrounding neighborhood consists of import/export, aviation and other businesses. It is a good location for metal artisans. No one complains about the constant banging of hammers against metal barrels. Moreover, discarded barrels can sometimes be found at shops in the district.

In a field of sawgrass behind a warehouse complex on the edge of Miami's suburban Tamiami Airport, Michael Kernahan creates high-precision musical instruments, known as pans, from discarded oil and chemical barrels. He works in a small clearing under a tree that provides some limited shade. Assorted barrels are stacked around the space-some are full size, while others have been cut. A briefcase filled with metalworking tools rests on one barrel. From the edge of the clearing, a narrow path extends to another space, where pans are heated over a wood fire. In the distance is a third clearing, in which Kernahan's apprentice, Michael Phillip, sometimes works. This outdoor workshop is a peaceful place. Breezes blow across the acres of sawgrass, while occasional helicopters and small planes take off from the airport. The surrounding neighborhood consists of import/export, aviation and other businesses. It is a good location for metal artisans. No one complains about the constant banging of hammers against metal barrels. Moreover, discarded barrels can sometimes be found at shops in the district.

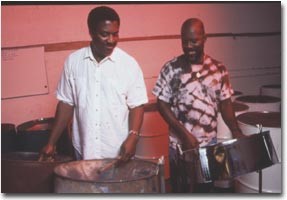

One of the warehouse units next to the field where Kernahan works is the panyard or headquarters of the 21st Century Steel Orchestra. In addition to tuning (fabricating) pans, Kernahan serves as the leader and musical arranger for this band. He also plays an instrument known as the double second pans. While most individuals associated with the pan world today specialize in tuning, arranging, playing or administration, Kernahan follows in the tradition of the old-time pan leaders of Trinidad who combined all of these activities. His versatility and accomplishments have earned him great respect from other pan musicians. At a recent party in 21st Century's panyard, numerous members and supporters of the band took turns testifying about the multifaceted impact that Kernahan has had on the pan world. "We all can consider it a real privilege to have known him," suggested one panman. Indeed, Kernahan has inspired audiences throughout North America with his music, has taught countless students to play pans, has tuned instruments for numerous steelbands in Florida and other states, and is now patiently passing on his vast knowledge of tuning to his apprentice. In short, he has been one of the guiding forces in Miami's still emerging pan scene.

Steelbands, a creation of the twin-island nation of Trinidad and Tobago, are a relatively recent phenomenon in South Florida. Though a few pannists, such as the internationally known jazz virtuoso Othello Molineaux, were active in Miami by the early 1970s, most have arrived during the past twenty years, as part of a growing migration of Trinidadians and other West Indians to the region. Pannists have performed as part of small ensembles in the tourist industry and private party market, as well as playing with steelbands for the local Caribbean Carnival and other community events. Among the steelbands in Miami at present are 21st Century, Rising Star, Miami Pan Symphony and Miami Steel. There are also some school bands, most notably an ensemble at Florida Memorial College under the direction of Dawn Batson, a pan educator and arranger with many accomplishments in both Trinidad and the United States. Along with these bands, there are a number of individual pannists who play in restaurants, on cruise ships and at other venues.

The characteristics of the Miami pan scene and of Michael Kernahan's remarkable career are best understood in the context of the development of pan music in Trinidad. What was once a disreputable type of street music eventually became a cherished national art and a new form of musical expression for the world.

The Historical Development of Pan

The musical form that is now known as "pan" emerged during the late 1930s in Trinidad. Its immediate precursor was African-Trinidadian tamboo bamboo music, which was played by striking different sized pieces of bamboo together or stamping them on the ground during pre-Lenten Carnival street processions. During the 1930s tamboo bamboo men began beating on metal containers (such as paint and trash cans), automobile parts and other metal objects. This metallic percussion proved to be louder and more durable than bamboo; around 1940 Carnival bands began to discard their bamboo altogether. During this period it was discovered that the bottoms of metal containers could be pounded into various shapes to produce musical tones when struck with sticks. Performance on different types of early pans was modeled on the roles of the diverse instruments of the tamboo bamboo band, though there was also influence from military marching bands, African-derived skin drums and, perhaps, East Indian-derived tassa drum ensembles. The earliest steelbands essentially provided a polyrhythmic background for the singing of Carnival revelers.

The creators of pan were primarily young and from the "grass-roots" (low-income) sector of the society. Steelbands were based in various urban neighborhoods and villages, and intense rivalries ensued as panmen developed their new instruments. Following World War II, panmen often named their bands after movies, such as Casablanca, Destination Tokyo, Cross of Lorraine and Desperadoes. During Carnival the bands paraded the streets, often masquerading as sailors, and sometimes engaged in violent clashes. Panmen and their music were widely condemned by the middle and upper classes and even by many members of the working class. However, by the late 1940s there were some prominent civic leaders, artists and politicians who began promoting the steelband as an indigenous art form and arranged for bands to play in concert settings. Meanwhile, a steelband association was organized and middle-class youths began forming bands of their own.

By the 1950s steelbands had become an integral part of the cultural life of the colony, performing everywhere from elite social clubs to nightclubs for sailors and tourists to weddings and christenings in grass-roots communities. When Trinidad and Tobago achieved its independence from Britain in 1962, the steelband was already an important national symbol. During the 1960s businesses began to sponsor steelbands and state support for the movement grew. By the 1970s pan instruction was being offered in a number of schools, a development that encouraged women to join bands.

The institutionalization of the steelband movement was paralleled by a transformation of the music. In the course of the 1940s more notes were added to pans by grooving additional sections on the bottoms of containers and, by the end of the decade, the full-size oil barrel had become the most popular source of instruments. Meanwhile, the tonal quality of pans improved and the wrapping of the ends of playing sticks with strips of rubber helped to create a mellower sound. By the early 1950s the different types of pans (each with its own register) contained sufficient notes to make conventional Western harmony possible. While steelbands played only simple melodies during the World War II period, by the early l950s they were performing a variety of local calypsos, Latin American musical genres (such as mambos, boleros and sambas), North American popular songs and European classical selections. Steelbands have continued to maintain eclectic repertoires up to the present.

In Trinidad today there are more than 100 steelbands, ranging from massive orchestras with 100 members to small ensembles. The premier performance occasion for bands is the multi-round Panorama competition that is held during the Carnival season. Bands also perform in street processions during the Carnival, at other competitions and in a variety of community events.

Though the steelband movement has its most vibrant manifestation in Trinidad, pans are also played in many other countries. The use of pans first spread to other parts of the anglophone Caribbean during the 1940s, through migration to and from Trinidad. By the 1950s there were steelbands in immigrant communities in New York and London. Gradually, steelbands were established in other cities of the West Indian diaspora. Meanwhile, the presence of many West Indian pannists abroad and the distribution of steelband recordings inspired non-West Indians to form steelbands. In the United States, for example, there are numerous bands associated with colleges, high schools and elementary schools. Steelbands can also be found in such countries as Venezuela, Switzerland, Nigeria and Japan.

A Career in Pan

Michael Kernahan is one of the many pannists who have left Trinidad in search of musical opportunities, adventure and, ideally, some income. At first he toured North America with a steelband; later he settled in the United States on a permanent basis. However, he continues to maintain close ties with Trinidad and returns for visits on a regular basis. His many contributions to pan in the U.S. are based on his firm foundation and extensive education in the Trinidadian pan tradition.

Michael Kernahan is one of the many pannists who have left Trinidad in search of musical opportunities, adventure and, ideally, some income. At first he toured North America with a steelband; later he settled in the United States on a permanent basis. However, he continues to maintain close ties with Trinidad and returns for visits on a regular basis. His many contributions to pan in the U.S. are based on his firm foundation and extensive education in the Trinidadian pan tradition.

Kernahan was born in 1947 in Palo Seco, a small village in southern Trinidad. While a child, he moved to Manzanilla on the island's eastern coast and, around 1960, ended up in the St. James neighborhood of Port of Spain (the capital of Trinidad and Tobago). Though he missed country life, his encounters with pan kept him tied to the city. During this period St. James was the home of many fine steelbands, including the famous Tripoli Steel Orchestra. Kernahan was fortunate to have cousins who were members of Tripoli, and he soon started playing with the band, in spite of his parents' opposition. Even though pan was a widely appreciated form of music by this time, many Trinidadians still viewed panmen as disreputable and prone to violence and crime. Kernahan recalls:

I started to play in Tripoli in 1964. My parents didn't know anything about that. I remember it was Carnival 1964. We were coming up the Tragarete Road, right by the Lapyrouse Cemetery [in the Woodbrook neighborhood of Port of Spain]. My mother was on the sidewalk. She saw me playing and she started to cry. She came in the band. Well, I had a cousin, he was an older guy. Luckily, my mother always believed in him. So he told her: "Well look, now, it's all right. I'm going to take care of him." Because she started crying and saying: "Oh lord, my son is a vagabond." You know, just now you start to walk with knife in your pocket. And she was really crying. I felt bad. But, when he talked to her and kind of calmed her down a little, it was all right. I continued playing until now. I never got in no trouble, and I never walked with a knife.

During the mid-1960s Tripoli was in its heyday: it played on the streets for Carnival with legions of followers and at so many Carnival fetes (parties) that it often had to split into more than one section in order to fulfill all of its engagements. The band was also a regular competitor at the steelband festival that was held in the elite Queen's Hall at the time. Through their sponsor, the Esso oil company, over twenty members of the band, including Kernahan, were able to go on an overseas tour and play at Expo '67. Before arriving in Montreal, they played in several parts of the West Indies and in New York, with appearances in Lincoln Center and on the Ed Sullivan Show. Throughout the summer they performed at the fair's Trinidad and Tobago pavilion and were a phenomenal success. During this engagement they also recorded an album-The Esso Trinidad Steelband On Tour-which included such tunes as "The Blue Danube," "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik," "Michelle," and "No Money, No Love," a calypso by the Mighty Sparrow.

Sales for this album were so strong that the following summer Tripoli was able to leave Trinidad on another tour, following the same path as before. This time the members appeared in the Expo '67 reprise, called "Man and His World." While performing they were visited by a fan from the previous year: Liberace. This encounter led to one of the more unusual chapters in steelband history. Liberace was so captivated with the pan sound that he contracted Tripoli to accompany him on tour. The band became a regular feature in his extravagant shows in top concert halls from Los Angeles to New York. Kernahan recollects:

We came out at a certain point in the show. He would introduce the band. We did two songs by ourselves and then we did [two] with him: "Alley Cat" and "Twelfth Street Rag." It was a great thing. Every night it was something else: we got a standing ovation. We did songs like "Poet and Peasant Overture," "Die Fledermaus." Now and then we'd do the "Hallelujah Chorus." . . .

That went on for two years [until 1970]. And luckily, again, we were the only act that he kept for that long. He had people like Barbra Streisand-he'd put them out in just like one year. But he kept us. It was a really good thing that was going. . . . He had always had something strange on his show. Something different. He liked the pan, but his manager didn't want it at all. And he [Liberace] said: "No, this is what I want."

When the engagement with Liberace ended, Tripoli continued to tour the country on their own. In 1971 they recorded an album for Warner Brother, The Esso Trinidad Steel Band, which was nominated for a Grammy Award in 1972. That same year the band returned to Trinidad.

Back home Tripoli was able to further capitalize on its reputation by obtaining a gig as the resident band at Port of Spain's Holiday Inn and by playing on the docks for visiting cruise ships. The members were actually able to make a living from playing pan, which was fairly unusual in Trinidad, even during this period when steelbands were regularly hired for fetes and other functions.

Meanwhile, Kernahan found himself with some spare time and decided to experiment with tuning pans:

There was no water coming up the hill [where his father lived]. Bob [Thomas], a tuner in town-he gave me six [oil] drums to take to my father, so you could put water in. But my father only ended up getting one. He gave me the six drums, and I went out and buy a hammer, a sledge. I going to try my hand at doing something. Well, I burst about four of them. I didn't know what I was doing. One came out-to me it was looking all right. But I tried to tune it, and it didn't come out right.

So what I did, I decided I would bring it in town. When Alan [Gervais, Tripoli's expert tuner] comes, I'm going to show it to him. I took it to town and he came. I tell him I was trying to make a pan. He said: "Well, let me see what you did." I showed him it, and he started to laugh. He said: "All right, I'm going to show you." He started teaching me. Before long, I started doing like cello and guitar pans [types of pans]. I didn't take long because I think he was a good teacher. Because he always said: "I'll make you a tuner real fast." He always said that. Maybe because I did [automobile] body work, I already knew how to really hammer. So it didn't take me long to catch up.

Though he was progressing quickly, Kernahan felt that he was still not ready to provide any steelbands with pans. But in 1975 he had the responsibilities of pan tuning and "blending" (re-tuning) thrust upon him and, at the same time, had an inauspicious introduction to Miami:

This guy approached us to come to Miami for ten days. Alan [Gervais] was supposed to come out as the tuner, but he was already committed to go to Switzerland with Solo Harmonites [another top steelband]. That's when he said: "Well, you'll have to take charge as a tuner." So we left Trinidad. We packed up all the pans and got here. I was the tuner. There were ten of us [all Tripoli members]. I'll tell you something: that was one of the strangest experiences we ever had. This guy brought us to Miami. We got to Miami. We were put up in a hotel on the beach. And we never saw the guy again. We were just here in Miami doing nothing. We were here for two weeks doing nothing. We tried to get in touch with people and we organized a few little places to play.

Fortunately, the brother of one of the band members called from Michigan and said that they could obtain work up there. As a result of this call, Kernahan and several members of Tripoli ended up settling in Michigan, where they re-grouped as the "21st Century Steel Band." This ensemble obtained steady work into the 1980s, playing at colleges, fairs and other venues throughout the country. But Michigan's harsh winters were increasingly a burden and it was difficult to find work during that time of the year. By the mid-1980s they decided to give South Florida a second chance and started visiting every year. Among their gigs was one at the Dade County Youth Fair, booked by an agent in Michigan. Eventually, Kernahan, his wife and four members of the band settled permanently in Miami.

Over the years Kernahan has devoted more and more time to tuning. In addition to making pans for bands and individuals in Florida, he has tuned for school bands in Michigan, Illinois, Mississippi and South Dakota. The phone is always ringing in the Kernahan residence, with inquiries from as far away as Belize and Guyana. He even found himself tuning pans on a recent "vacation" back to Trinidad for Carnival.

The Tuning of Pans

Tuning a pan or set of pans is a complex process that takes many hours of work, generally spread over a period of at least two days. The first step is to obtain 55 gallon barrels. Pan instruments vary in terms of the number of barrels required, the number of notes on the playing surface, the depth of this surface when hammered into a concave shape, and the length of the "skirt" (the sides of the pan). The pans that Kernahan generally tunes include tenors, double seconds, double guitars, triple guitars, tenor basses and six basses (see Table 1 and Figures 1 - 6).

Tuning a pan or set of pans is a complex process that takes many hours of work, generally spread over a period of at least two days. The first step is to obtain 55 gallon barrels. Pan instruments vary in terms of the number of barrels required, the number of notes on the playing surface, the depth of this surface when hammered into a concave shape, and the length of the "skirt" (the sides of the pan). The pans that Kernahan generally tunes include tenors, double seconds, double guitars, triple guitars, tenor basses and six basses (see Table 1 and Figures 1 - 6).

Though each pan instrument has its unique features, the basic tuning principles are the same. The procedures that Kernahan uses for tuning a tenor pan can serve as an illustration. This instrument requires a barrel with 18 gauge metal on the top and bottom and thinner 20 gauge metal on the sides. Once obtained, the barrel is turned upside down, with the top resting on the ground. (Since the barrel's top has a bunghole for removing its contents, the bottom is used for pan tuning.) The bottom of the pan is sunk inward, using both a bowling ball and a sawed-off 12-pound sledge hammer. Once the surface has begun to assume a concave shape, a pencil and ruler are used to make some preliminary markings of individual sections, each of which will become a note. Sinking then continues with a 40-ounce hammer (with a shortened handle). Eventually, the surface of the pan is cleaned and the section markings re-drawn to form three concentric circles of notes, totaling 30. The sinking process concludes when the pan has reached a depth of 7.25 inches and the metal is "tight."

The next step of the tuning process is to "groove" the individual note sections with a 24-ounce hammer and a nail punch with a blunted point. By carefully hammering the punch, a shallow indentation is made around the perimeter of each section. After finishing the inner sections, the surface is again hammered to remove any looseness from the metal and to pull it back toward the sides of the barrel. Without this additional hammering, one might puncture the metal when grooving the outer sections.

When all of the sections have been grooved, the pan is ready to be cut. This can be done either with an electric jigsaw or a hammer and chisel. A cleaner cut is then made with a pair of scissors until the skirt of the pan is 5.5 inches long. Next the pan is heated in a wood fire to release stress in the metal. One half of a discarded barrel serves as a furnace. Once the fire is blazing, the pan is rested in the flames. In the course of the usual three to seven minutes of heating, the pan is shifted from time to time to ensure that all parts of the surface are affected.

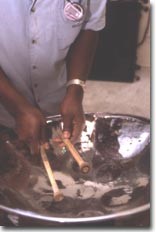

After the pan has cooled, the actual tuning of notes can begin. Like most tuners, Kernahan uses an electronic tuning device: a Korg Chromatic Tuner with a range of three octaves. Before tuning the notes, however, the individual sections have to be "ponged up" from underneath the pan. First, the sections on the outside perimeter of the pan are prized up with a 2x4 piece of wood, wedged against the pan skirt. This process helps to separate the note sections from the rest of the pan's surface, thus allowing them to vibrate and sound. When the outside sections have been ponged up, the pan is rested on an automobile tire, with the playing surface facing up. The notes are then tuned with a 24-ounce hammer and a pan playing stick, which, in the case of a tenor pan, is approximately 7 inches in length and has a tip wrapped with a piece of rubber. As Kernahan strikes an individual section, one can hear the note moving up and down in pitch. Strikes to the center of the section lower the note, while those to the edge have the opposite effect. At times, the pan is turned upside down and hammered from below or even ponged up again. Kernahan periodically compares the pitch from each pan section with the corresponding pitch selected on the electronic tuner. At this point, he simply tries to place all of the outside notes at their approximate pitches.

An even more complicated part of the tuning process involves amplifying the harmonics or overtones of each note. Over the years tuners have perfected techniques of hammering certain parts of a note section to bring out fifths and octaves above the fundamental. This must be done uniformly for all notes, if the pan is to have a consistent tonal quality.

After working on the outside notes, Kernahan pongs up the inner sections with a hammer and proceeds to tune them. This invariably affects the outside notes. Thus, he must keep working with the inside and outside notes until all of them correspond to the required pitches and have consistent harmonics. When the pan is fully tuned, it is cleaned with acid and taken to a metal shop where it is chromed. Chroming hardens the metal and helps the pan to retain its tones. While tenors and double seconds are routinely chromed, other pan instruments are usually painted, due to the expense of chroming large amounts of metal.

In addition to tuning the variety of pans used by a steelband, Kernahan also builds metal stands for suspending all of the instruments except the basses. Basses are rested on wooden blocks when played. It is also necessary to make playing sticks, which vary in length, diameter and the amount of rubber on their ends. For example, portions of rubber balls are generally attached to bass sticks. If pans are kept indoors and periodically cleaned, they will last many years. But, with regular use, their notes eventually fall out of tune. Thus, from time to time, one must re-tune all of the notes on all of the pans in a steelband.

In addition to tuning the variety of pans used by a steelband, Kernahan also builds metal stands for suspending all of the instruments except the basses. Basses are rested on wooden blocks when played. It is also necessary to make playing sticks, which vary in length, diameter and the amount of rubber on their ends. For example, portions of rubber balls are generally attached to bass sticks. If pans are kept indoors and periodically cleaned, they will last many years. But, with regular use, their notes eventually fall out of tune. Thus, from time to time, one must re-tune all of the notes on all of the pans in a steelband.

For Kernahan there is always more work to be done. When not tuning pans for 21stCentury, he is busy tuning for other bands and pannists throughout South Florida and beyond. His tuning is an almost meditative process. While working he is highly focused, carefully engaging the metal with his tools and listening to nuances of sound. This deep feeling and appreciation for metal connects him to the long tradition of great tuners from Trinidad. From time to time, he puts down his hammer and talks about these masters-their many discoveries over the years and their ceaseless efforts to perfect their instruments. Pan tuning is something very tricky, he concludes, and something that one must keep doing all the time. With each pan, one learns something new.

The 21st Century Steel Orchestra

Since re-locating to South Florida, Kernahan's 21st Century Steel Orchestra has grown in size. Over the past five years, a number of local pannists have joined the band, several of whom had previous experience with pan in Trinidad. 21stCentury has its largest contingent of performers during the Miami Carnival, which is held on Columbus Day weekend. During the 1998 Carnival, for example, the band included 35 players: 6 tenors, 6 double seconds, 1 quadraphonic (an instrument consisting of 4 pans), 5 double guitars, 3 triple guitars, 4 six-basses, and an "engine room" section of traps, congas, bongos, cowbell and 6 "irons" (automobile brake drums). For other engagements, far fewer players are used. The band's 1996 Christmas concert at the Joseph Caleb Auditorium in Miami, for example, featured 14 musicians. Between 5 and 10 players are used for most events, such as civic festivals, museum concerts, private parties, and the Trinidad and Tobago Independence Day Mass at Miami's Trinity Episcopal Cathedral.

Like steelbands in Trinidad, 21st Century has a diverse repertoire of music. Among their many tunes are calypsos, such as Sparrow's "Birthday Party," Kitchener's "Iron Man" and Robert Greenidge's "Fire Coming Down." American popular tunes include such selections as "Moonlight in Vermont," "You Go To My Head" and "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas." European classical pieces that they frequently play are Handel's "Hallelujah Chorus," Strauss's "Voices of Spring" and von Suppé's "Poet and Peasant Overture." Original compositions include Kernahan's funk-influenced "Mess Around" (see Musical Example 1) and a calypso titled "What Is a Pan?." Given this range of musical selections, the band is able to perform for a variety of occasions and audiences.

In addition to playing double seconds in 21st Century, Kernahan arranges all of the band's music. He started to perfect his arranging skills during the 1970s and notes that he has been influenced by four of the finest arrangers in Trinidadian pan history: Junior Pouchet, Beverly Griffith, Ray Holman and Earl Rodney. Pouchet led and arranged for Silver Stars in Trinidad during the 1950s and 1960s and also arranged for Tripoli for a brief period. Since 1971 he has led a small pan ensemble at Disney World in Orlando. Since the 1960s Griffith has periodically served as an arranger for Desperadoes, one of Trinidad's premier steelbands. He currently resides in South Florida, where he plays in small combos. Holman lives in Trinidad and has arranged for numerous top steelbands, such as Starlift, Invaders and Tokyo. Rodney also lives in Trinidad and is renowned for his arrangements for Harmonites and for the Mighty Sparrow, the calypsonian. For his own arrangements, Kernahan draws on the smooth, lyrical styles of all four of these masters. He also continues to play some old Tripoli arrangements, such as Pouchet's interpretation of Gershwin's "The Man I Love."

Though 21st Century performs around the year, the Miami Carnival season is the period during which the band is most active. Miami's Carnival draws tens of thousands of participants from Florida, northern cities and the West Indies. It is, in fact, the grand finale of an annual cycle of Carnivals that are held throughout the West Indian diaspora, all of which are modeled on the pre-Lenten Carnival in Trinidad. The climax of the Miami festival is the street parade on the Sunday before Columbus Day. During the weeks leading up to this event, there is much activity in the West Indian community:mas (masquerade) bands prepare their costumes in their camps, calypsonians and "brass bands" perform at fetes, and steelbands rehearse the calypsos that they will perform in the local Panorama competition on the Saturday night before the parade. Steelbands also play in the parade itself, though the music for most of the mas bands is provided by deejays and brass bands, ensembles that include guitars, keyboards and percussion, as well as horns.

Like other steelbands, 21st Century spends several weeks preparing for the Panorama and Carnival parade. In addition to cleaning and painting pans, it is sometimes necessary to build new mobile "racks" for moving the pans onto the Panorama stage and through the streets. Racks are made by welding pieces of metallic electrical tubing together to form a frame for suspending the pans, covering this structure with a sheet metal canopy and attaching wheels. Friends of the band often drop by to assist with the preparations and to listen to the late-night rehearsals.

Kernahan follows traditional practices in developing a Panorama musical arrangement. After selecting a calypso that was sung in the most recent Trinidad Carnival, he works out musical parts for each section of pans. These parts are taught by ear to the section members phrase by phrase. Typically, the tenors play the melody, the double seconds play a harmonization of the melody or "strum" chords, the guitars strum chords and play short runs, and the basses provide the bass line. The other percussion instruments in the band maintain a basic beat and generate dense polyrhythms. Musical phrases are drilled by the individual sections of pans and then by the whole band for hours until they are committed to memory. Over the course of a few weeks, new material is gradually added. The finished arrangement is usually ten minutes long and comprises an introduction, the calypso verse and chorus, variations on the verse and chorus, and an ending. Often the arrangement includes counterpoint (the interweaving of different melodic lines), the shifting of the primary melody to different sections of pans, and key modulations.

The Panorama and Carnival have been held in different locations around Miami, most recently at the Hialeah Racetrack and the Opa-locka Airport. For the Panorama, 21st Century and the other competing bands perform on a stage in front of a panel of judges and an audience of steelband enthusiasts and general revelers. The evening's entertainment also includes a competition for the finely crafted costumes of the "Kings," "Queens" and "Individuals" from the various mas bands. The following day the steelbands join the mas bands for hours of festivity on the surrounding streets. Steelband supporters help push the racks of pans through the streets and dance to the invigorating rhythms of the calypsos. Some join the bands by beating rhythms on pieces of metal. The Miami Carnival, like all Trinidadian-style Carnivals, represents a dazzling blend of tradition and innovation in masquerade and music. Each year creativity and revelry are pushed to the limits as people celebrate the human capacity for expression and communion. After the sun sets, the participants' energy begins to subside and they eventually wander home. 21st Century loads its pans and racks into a semi-truck and heads back to its panyard. Though the Miami Carnival is over, there are other engagements to play and the Carnival season in Trinidad is only a few months away.

On most days Michael Kernahan can be found at 21 Century's panyard. Usually he carries out the fine tuning of new pans in the warehouse, surrounded by the band's pans, racks and equipment. In a loft above the rehearsal space is his office. On a desk is the paperwork generated by a career of making pans and managing a band. An answering machine records messages for a phone that rarely can be heard above the sounds of rehearsals and pan tuning. In one corner of the room is a stack of vintage calypso and steelband albums, including some of Tripoli's masterpieces. Though always overburdened with work, Kernahan is never too busy to welcome a visitor and to reminisce about some of the adventures of his life in pan. He looks over a few old Tripoli photographs and recalls the many personalities he has met through the years. Across from his desk are a tenor pan and a pair of double seconds, tuned by his deceased mentor, the great Alan Gervais. He walks over and plays a few runs; though the pans are over twenty years old, their tone is as rich and pure as ever. Kernahan says that he loves these pans and that, until a few years ago, he continued to use them at gigs. Now they serve both as a model and inspiration for his own work as a tuner:

I try to stick with it [the Gervais method]. Why I could relate close to it is because I still have some of his instruments. So I could go back and try to keep it like that. . . . I've met people, Trinidadians, they come around and say: "Boy, Alan really taught you." It looks like his work.

Though Kernahan perpetuates his mentor's techniques, he has also developed his own style. He ceaselessly explores ways of improving the sounds of pans so that they will continue to captivate audiences in South Florida and around the world. For him, each pan, like each musical arrangement, is a new experiment.

Suggested Reading

Allen, Ray and Les Slater. "Steel Pan Grows in Brooklyn: Trinidadian Music and Cultural Identity." In Island Sounds in the Global City: Caribbean Popular Music and Identity in New York, ed. Ray Allen and Lois Wilcken, pp. 114-137. New York: New York Folklore Society and Institute for Studies in American Music, Brooklyn College, 1998.

App, Lawrence J. "The Professionalization and Commodification of Steel Drum Music in Florida: Musical Continuity and Change in the Caribbean Diaspora." M.A. thesis, Florida State University, 1997.

Averill, Gage. "'Pan Is We Ting': West Indian Steelbands in Brooklyn." In Musics of Multicultural America: A Study of Twelve Musical Communities, ed. Kip Lornell and Anne K. Rasmussen, pp. 101-129. New York: Schirmer Books, 1997.

Batson, Dawn Kirstin. "Pan Into the 21st Century: The Steelband as an Economic Force in Trinidad and Tobago, " Ph.D. dissertation, University of Miami, 1995.

Goddard, George "Sonny." Forty Years in the Steelbands: 1939-1979, ed. Roy D. Thomas. London: Karia Press, 1991.

Hill, Errol. The Trinidad Carnival: Mandate for a National Theatre. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1972.

Molineaux, Othello. Beginning Steel Drum. Miami: Warner Bros. Publications, 1995.

Stuempfle, Stephen. The Steelband Movement: The Forging of a National Art in Trinidad and Tobago. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995.

Thomas, Jeffrey. "Steel Band/Pan." In Encyclopedia of Percussion, ed. John H. Beck, pp. 297-331. New York: Garland Publishing, 1995.

For performances of "What Is a Pan?" and "Mess Around" by the 21st Century Steel Orchestra, see Caribbean Percussion Traditions in Miami. CD recording. Miami: Historical Museum of Southern Florida, 1999.