History

I. Settlement and Transportation in Spanish Florida

From the time Pedro Menéndez de Avíles founded St. Augustine in September 1565, Spanish authorities began to extend their reach into the surrounding territories, with St. Augustine serving as the military, administrative, and religious headquarters of Spanish Florida.

From the time Pedro Menéndez de Avíles founded St. Augustine in September 1565, Spanish authorities began to extend their reach into the surrounding territories, with St. Augustine serving as the military, administrative, and religious headquarters of Spanish Florida.

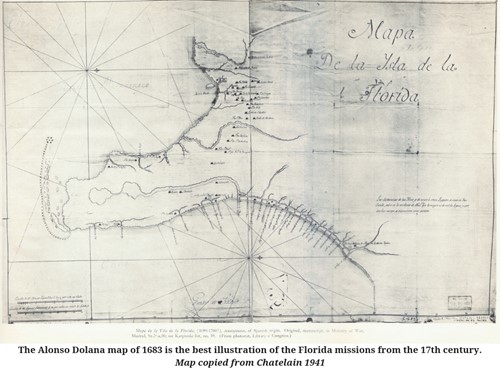

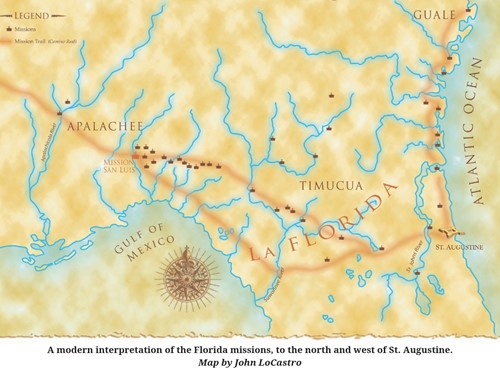

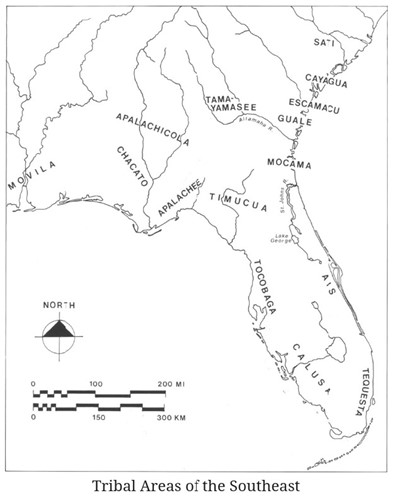

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Franciscan friars established more than a hundred missions among the native populations. Although Spaniards attempted to reach indigenous populations throughout the Southeast, the Indians of north Florida and south Georgia (the Timucua, Mocama, Guale, and Apalachee) were most receptive to the friars’ religious message. Religious conversion was often followed by building of Spanish forts and ranches, and as the colony grew, so did the need to move people and supplies across the frontier, to and from St. Augustine.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Franciscan friars established more than a hundred missions among the native populations. Although Spaniards attempted to reach indigenous populations throughout the Southeast, the Indians of north Florida and south Georgia (the Timucua, Mocama, Guale, and Apalachee) were most receptive to the friars’ religious message. Religious conversion was often followed by building of Spanish forts and ranches, and as the colony grew, so did the need to move people and supplies across the frontier, to and from St. Augustine.

During most of the 17th century, overland transportation into and out of St. Augustine ran in two primary directions—north and west. Sea lanes and rivers were also used extensively, but even the “inland” path required ferry transportation of people, animals, and cargo across the rivers. Whether travel was overland, or by water, native peoples provided the labor needed for transportation throughout La Florida.

During most of the 17th century, overland transportation into and out of St. Augustine ran in two primary directions—north and west. Sea lanes and rivers were also used extensively, but even the “inland” path required ferry transportation of people, animals, and cargo across the rivers. Whether travel was overland, or by water, native peoples provided the labor needed for transportation throughout La Florida.

The route to the north along the Atlantic coast was established to serve the Mocama and Guale missions and military outposts in present-day northeast Florida and southeast Georgia. Travelers had to cross the St. Johns River by ferry at Mission San Juan del Puerto, located on present-day Fort George Island. From this point, they often took advantage of the Inland Passage (today’s Intracoastal Waterway) to reach the coastal Mocama and Guale missions.

The route to the north along the Atlantic coast was established to serve the Mocama and Guale missions and military outposts in present-day northeast Florida and southeast Georgia. Travelers had to cross the St. Johns River by ferry at Mission San Juan del Puerto, located on present-day Fort George Island. From this point, they often took advantage of the Inland Passage (today’s Intracoastal Waterway) to reach the coastal Mocama and Guale missions.

The westward mission trail to Apalachee Province and beyond required crossing the St. Johns River at the San Diego de Salamototo mission (near present-day Orangedale). After then crossing the Alachua Plain, travelers had to be ferried over the Suwannee River. This was followed by another overland trek through western Timucua Province, over the Aucilla River, and into Apalachee Province.

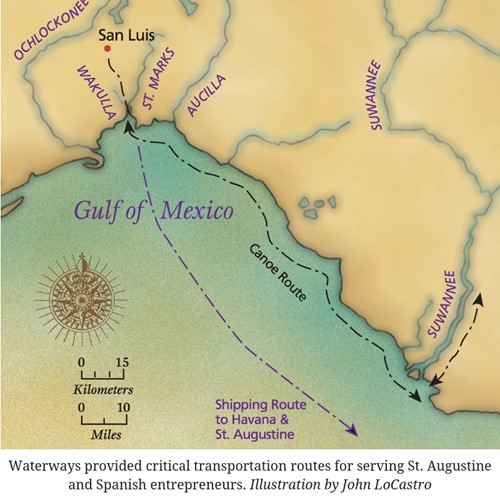

Wherever possible, waterways were the preferred means of transportation. A common route for transporting corn and other heavy cargo from Apalachee to St. Augustine was to first move it west (via river or land) to St. Marks. From there, it was taken by canoe down the coast and up the Suwannee River, from where it ultimately moved overland to the capital. Cargo could also be transported via sea lanes around the peninsula to St. Augustine or to Havana, Cuba, where handsome profits were made by Spanish ranchers.

Wherever possible, waterways were the preferred means of transportation. A common route for transporting corn and other heavy cargo from Apalachee to St. Augustine was to first move it west (via river or land) to St. Marks. From there, it was taken by canoe down the coast and up the Suwannee River, from where it ultimately moved overland to the capital. Cargo could also be transported via sea lanes around the peninsula to St. Augustine or to Havana, Cuba, where handsome profits were made by Spanish ranchers.

II. Building the Road

It was not until the 1680s that the Spaniards decided to build a formal road connecting St. Augustine with the missions across north Florida, granting military engineer Enrique Primo de Rivera a contract for road construction between St. Augustine and Mission San Luis (in present day Tallahassee). The missions between these two locations served as way-stations for travelers, providing them food, shelter, and assistance during their journey.

Building the road required clearing large amounts of vegetation to create a path wide enough for carts and pack animals. Swampy areas and spongy river banks were also filled in to make them passable, but they were impossible to maintain, as were the roads themselves. While the weight of the carts helped compact the dirt roads in the dry season, they developed large ruts and eroded during periods of heavy rainfall.

Primo de Rivera succeeded in completing only part of the road, the western portion from Mission San Luis to Mission San Francisco de Potano (near today’s Gainesville), before terminating his contract. The following excerpt from a letter from the Florida Governor to the King indicates that the engineer encountered too many natural obstacles to overcome:

…he was not able to manage [because of their poor preparation—poco o mal auio] to travel some twenty leagues from here [St. Augustine] with its being necessary for him to open and to repair some pieces of the road of arroyos [streams] and swamps, even though the general part of it and all of it, according to what I have seen on the said visitation is suitable for the passage of wagons. As a result it ceased completely and for everything with the said trip begun and he abandoned the obligation because of not being able to achieve it…

Written by Florida Governor Diego de Quiroga y Losada to the King of Spain in St. Augustine on April 1, 1688, and received on November 27 of that same year. Translated by John H. Hann, Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research, Division of Historical Resources.

To date, there are no records indicating any further effort to finish the formal road between the Gainesville area and St. Augustine, although mules, packhorses, and people continued to use this primary route. There are also no exact descriptions of the Camino Real, and we know only that it was wide enough to accommodate wagons, which were generally about eight feet in width.

Spanish Florida’s Camino Real did eventually expand west from Mission San Luis to Pensacola after it was founded in 1698. Early thoughts of possibly extending it all the way to Mexico never materialized.

III. The End of the Florida Missions

In 1702, British Carolina Governor James Moore launched a full-scale attack on Spanish Florida. Many of the missions on the Atlantic coast were destroyed, along with the town of St. Augustine. The Castillo de San Marcos, however, proved to be impenetrable and most of the town’s residents remained safely within the fort walls while St. Augustine was under siege. In 1704, Moore turned his sights to Apalachee Province. During January and July of that year, all of the Apalachee missions were destroyed.

None of the Apalachee missions were ever reoccupied. In 1716, a decade after the last Timucua mission was abandoned, Diego Peña travelled the road from St. Augustine to the Apalachicola area. He went from the ruins of the Santa Fé mission (near present-day Miller), on to the remains of San Martín, and later the Guacara mission in present-day Suwannee County.

Diego Peña camped at several former mission sites during 1716 his trek:

The 19th day I left the said place and camped at the ycapacha [abandoned village] of San Martin [Boyd places this one league east of Ichectucknee spring].

The 20th day I remained at the said ycapacha because it was raining heavily and the Indians wished to hunt as we had no provisions. Here three buffalo and six deer were killed.

In Mark F. Boyd, Diego Pena's Expedition to Apalachee an Apalachicola in 1716. Florida Historical Quarterly 28(1):1-27. 1949.

He similarly reported killing three buffalo while later camping at the Mission San Luis site. The buffalo had moved into north Florida, where vibrant native villages and Spanish settlements had stood just years before.

IV. Territorial Period

On February 28, 1824, following the American occupation of Florida, the United States Congress appropriated $20,000 to build a public road extending from Pensacola to St. Augustine. In doing so, Congress referenced the mission-era Camino Real, which was to be used as a guide, when practical. Remnants of this 19th-century road, sometimes called the Bellamy Road (described below), are often mistaken for the 17th-century road:

…[from the Apalachicola River] thence in the most direct practicable route to the site of Fort St. Lewis; thence, as nearly as practicable, on the old Spanish road to St. Augustine, crossing the St. John’s river at Picolata; which road shall be plainly and distinctly marked and shall be of the width of twenty-five feet.

In Mark F. Boyd, The First American Road in Florida: Pensacola-St. Augustine Highway, 1824. The Quarterly Periodical of the Florida Historical Society 14(2):72-106. 1935.

Even the “new” 19th-century road linking St. Augustine and Pensacola was just a rough dirt road filled with tree stumps, and as cotton became increasingly important during the early 1800s, farmers found that the territorial road left much to be desired. Instead, they turned to Florida’s water routes and steamboats for transporting their produce to the northern markets and returning with supplies.